A pending invasion. Angry nobles. A new and nastier Holy Father. Mysterious disappearances. Not enough room to house refugees.

These are just a few of the troubles facing Queen Kelsea at the start of The Invasion of the Tearling, Erika Johansen’s second novel in The Tearling trilogy. It’s much darker than The Queen of the Tearling, but the pull of the story remains as strong as ever.

The Invasion of the Tearling takes on some pretty heavy social issues, and it doesn’t tiptoe around the nasty stuff. If you want trigger warnings, this book has: domestic abuse, spousal rape, and cutting.

The Invasion of the Tearling takes on some pretty heavy social issues, and it doesn’t tiptoe around the nasty stuff. If you want trigger warnings, this book has: domestic abuse, spousal rape, and cutting.

Like I said, it’s dark.

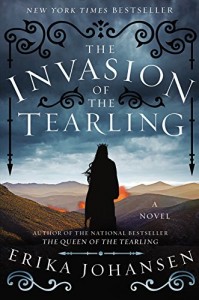

One of the overriding themes of the book is the continuing resilience of women across the ages.In this book, Kelsea finds herself repeatedly pulled back in time into the mind of a wealthy American woman from the late 21st century named Lily Mayhew. Kelsea finds a society vastly different from the Tearling, but there are some significant similarities. A literal wall separates the haves from the have-nots. Homosexuality has been made illegal. The church has significant power in the world of the wealthy. And most chillingly for liberal-minded female readers, women have become little more than baby-bearing property. Lily is among the masses of women not allowed to hold jobs, and the church and government shame her for not having children—birth control is technically illegal, but a thriving black market helps Lily attain the pill so she doesn’t have to bear the children of her domineering, intrusive husband who hits her semi-regularly.

Remember when I said this is all taking place later this century? If your skin’s not crawling, it should be, especially considering recent political moves concerning women’s rights.

But Lily discovers a potential escape from her life of horror: a separatist group called Blue Horizon, led by William Tear, is preparing to create a better world, and one of the members literally lands in her backyard and turns Lily’s world upside-down. The leader’s last name is no coincidence—readers know William Tear is the founder of the Tearling. Yes, the mystery of how the Tearling came to be finally starts coming to light!

But Lily discovers a potential escape from her life of horror: a separatist group called Blue Horizon, led by William Tear, is preparing to create a better world, and one of the members literally lands in her backyard and turns Lily’s world upside-down. The leader’s last name is no coincidence—readers know William Tear is the founder of the Tearling. Yes, the mystery of how the Tearling came to be finally starts coming to light!

Back in Kelsea’s Tearling, things are looking exceptionally grim, and the effect on Kelsea is extreme. Although she isn’t facing the same abuse as Lily, Kelsea’s resilience is still being tested as she tries to keep her identity in the face of great strife. In The Queen of the Tearling, we met a queen who was unquestionably good. In The Invasion of the Tearling, Kelsea is still striving to help her people—most notably women and the poor—but her methods have taken a darker turn. She knows she has a temper, so she tries to control her desire to inflict pain on the wicked and those who stand in her way by taking that rage out on herself. Her identity crisis is further deepened by her physical transformation. Although her magical sapphires previously appeared dormant (that is, before they started sending her back in time), there is no question they are the cause of Plain Kelsea turning into Kelsea the Beautiful. She believes the sapphires have granted her unspoken and much-suppressed wish to be pretty, but that just fuels her anger at herself for being granted something so petty, and her rage deepens.

And as if her determination to remain a force of good isn’t being tested enough, Kelsea is also tempted by a dark spirit who promises to tell her the key to destroying the invading Mort’s Red Queen … in exchange for its freedom. Kelsea knows in her heart this spirit is evil, but she’s also desperate to find a way to save her kingdom. She must decide if the greater good of saving thousands of innocent people from imminent slaughter is worth handing one agent of evil a small win.

Hmm. The greater good. Where have we heard that before?

Hmm. The greater good. Where have we heard that before?

In Kelsea and William Tear’s struggles to achieve the greater good, we see the cycle of history: a thriving society suddenly devolves into a nightmare that inspires a movement toward a better world. That movement, usually using violence, finally achieves its goal, creating a new society, which eventually devolves into another nightmare, and we come full circle. It’s a cycle Kelsea notices as she ping-pongs from the past to the present: “And Kelsea wondered suddenly whether humanity ever actually changed. Did people grow and learn at all as the centuries passed? Or was humanity merely like the tide, enlightenment advancing and then retreating as circumstances shifted? The most defining characteristic of the species might be lapse” (435).

The Invasion of the Tearling also shows the incredible strength of women across these cycles of history. In pre-Crossing America and in the Tearling, rape, abuse, and general mistreatment of women are commonplace. Lily isn’t the only woman we meet in America. We hear of her sister, a rebellious teen who was “disappeared” by the official Security agency—an Orwellian organization of torturers, censors and other soldiers of a despotic government. In Kelsea’s Tearling, we get the viewpoint of Aisa, the pre-teen daughter of a woman whom Kelsea saved from an abusive husband and who lives in the Keep with the queen. Aisa faced horror at the hands of her own father and is desperate to find some way to make herself feel safe.

These characters demonstrate how tough women can be, even those who think themselves weak. The Invasion of the Tearling is a powerful testament to the resiliency of the so-called softer gender. Each of the characters makes mistakes, sometimes grave ones, but ultimately they fight to overcome their fears and face their battles. None shies away when it’s her time to show her inner power.

Some people who have read this book have complained about the narrative bouncing back and forth between Kelsea’s and Lily’s stories. Others have objected to Kelsea’s physical transformation—admittedly, it was disappointing that our heroine didn’t stay plain, which was a nice contrast to the cliché of the beautiful queen everyone lusts after. And unlike The Queen of the Tearling, Kelsea does end up with something of a love interest in the sequel. However, it seems more realistic than some of the contrived love triangles of other series. Basically, Kelsea seeks an outlet for her urges, but she discovers that casual sex can foment some not-so-casual feelings. Finally, those who abhor anything remotely sacrilegious and believe the church and those who lead it are incapable of cruelty are likely to throw this book through the window.

Despite these objections, however, I thought the book was a fabulous commentary on modern society, from the challenges that face women to the church’s views of homosexuality. It also raises questions for us to ponder, both as individuals and as a society: Is cruelty ever an appropriate response to others’ cruelty? Is the proverbial deal with the devil still an act of evil, even when done to protect other people? And why is it that in many failing societies, women often become the primary targets of oppression?

Women continue to be strong and endure the unendurable no matter the terrors we face. Kelsea and a long list of other women in The Tearling books certainly prove that, and I count myself among the readers itching for The Fate of the Tearling, due out next June.

Cover image via Amazon. Protest photo via Buzzfeed. “Greater Good” created by Hannah Ritchie Stinger.