When I first saw Susan Bordo’s The Creation of Anne Boleyn featured at a local bookstore, I wanted to hate it.

You see, I wrote my undergraduate thesis on the exact same topic. Seriously. The massive 100+ page paper I spent more than a year pouring my life into remained unpublished, and now Susan Bordo had beaten me to the punch. But, my obsession with the Tudors and love for Anne Boleyn meant I had to buy the damn book.

As luck would have it, I ended up reading Bordo’s book at the same time Masterpiece Theater aired its six-part miniseries,Wolf Hall. The definition of history-nerd heaven: reading a book about representations of Anne Boleyn while watching one on TV.

To anyone who read or watched Wolf Hall and wants to know more about Anne Boleyn: The Creation of Anne Boleyn is a pretty good place to start. Bordo looks at Anne from a lot of different angles and maintains an engaging voice without sinking into academic “here’s a list of facts” dullness. The book isn’t straight history and doesn’t try to be completely objective. In fact, Bordo often admits her own thoughts on the subject so you know where she’s coming from. She doesn’t declare “this is unquestionably what happened” (most of the time), which I found quite refreshing.

The thing that is so fascinating and maddening about Anne Boleyn is that her story if full of love, sex, power, and death, but aside from the basic facts, we really don’t know that much about her. She grew up as the daughter of a man who had some status, but the Boleyns were sort of upstarts. There was no need to write about Anne when she was younger because her family wasn’t that important. Birth certificates weren’t really a thing in the 1500s, so we honestly don’t know if she was born in 1501 or 1507. Who cares, you might ask? Well, it either means Henry was casting aside his wife for a new, younger model, or that Anne was closer to him in age and he was more entranced by her mind. Maybe he wasn’t just going for a young woman, which adds all sorts of new layers to their relationship.

A lot of things about Anne fall into gray categories and can make her character take off in wildly different directions. Not to mention that she was the center of so much religious and political upheaval; her life practically begs for dramatic reinterpretation. Did she maliciously cause the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey, Henry’s most trusted advisor, because he thwarted one of Anne’s early romances? Who knows, but it makes for a good story (which is why a lot of books and movies suggest she did).

Bordo deftly analyzes the sources historians are forced to use when writing about Anne. Take historians’ reliance on the ambassador Eustace Chapuys and his account of Anne while he was at court. As a Spanish ambassador and proponent of Henry’s first wife, Chapuys hated Anne and took any opportunity to report malicious gossip about her. Is it true that the people loathed Anne and supported Catherine, or was Chapuys only thinking about the deeply devoted Catholic population? Chapuys also reported that Anne was trying to poison and kill the Princess Mary, but that seems like nothing more than petty gossip based on rumor.

Historians all note Chapuys is biased but then rely on him for information anyway. Why would they look at some of his reports with suspicion toward bias but then accept other rumors as fact? Thinking critically about how and why historians choose sources is incredibly important, and in the case of Anne Boleyn, her entire character hinges on the reports of a man who called her a “goggle-eyed whore.”

That’s not to say that Bordo doesn’t get in her own way sometimes. The insight she directs at other historians doesn’t always direct inward. History nerds who know about the argument surrounding a letter Anne allegedly wrote while in the Tower might scoff at Bordo for dismissing all criticism of its historical accuracy. But let’s instead focus on Henry and what Bordo thinks of him. What was Henry’s deal and why did he have his wife executed?

It’s important for a modern reader to remember that Anne was the first English queen to be executed. Other treasonous queens were usually just exiled or imprisoned. So, Bordo wants to look critically at Henry and figure out what made him decide to kill Anne. Digging into the psyche of historical figures is a dangerous game. Some observations can be made about Henry: he liked to get his way, he expected people to do what he said, etc. But Bordo goes on to theorize about what could have been happening in his mind and at one point suggests that borderline personality disorder best fits his actions. Sure, but given that she dismisses other people trying to psychoanalyze Henry, it’s odd for her to take a stab at it. Bordo shines best when she sticks to facts and history and possibilities. Talking about a medieval worldview when thinking about Henry works. Theorizing he had a psychological disorder doesn’t.

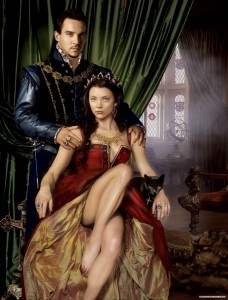

Her discussion of Anne’s portrayal in different books and movies is where Bordo departs the most from academics and starts engaging with versions of Anne that you might have seen or read. The two best sections concern Showtime’s The Tudors and the film adaptation of Anne of the Thousand Days. This is because Bordo conducted interviews with Michael Hirst, who wrote The Tudors, and Natalie Dormer, who portrayed Anne Boleyn in the show. Bordo also manages to interview Genevieve Bujold, who played Anne in Anne of the Thousand Days. Bordo gains great insight through these interviews and her conversation with Dormer about how the actress had to fight for a fair portrayal of Anne makes for riveting reading. Because these parts of the book are so strong, it’s disappointing when she skims over so many of the other portrayals (although her deconstruction of The Other Boleyn Girl is a lot of fun).

Her discussion of Anne’s portrayal in different books and movies is where Bordo departs the most from academics and starts engaging with versions of Anne that you might have seen or read. The two best sections concern Showtime’s The Tudors and the film adaptation of Anne of the Thousand Days. This is because Bordo conducted interviews with Michael Hirst, who wrote The Tudors, and Natalie Dormer, who portrayed Anne Boleyn in the show. Bordo also manages to interview Genevieve Bujold, who played Anne in Anne of the Thousand Days. Bordo gains great insight through these interviews and her conversation with Dormer about how the actress had to fight for a fair portrayal of Anne makes for riveting reading. Because these parts of the book are so strong, it’s disappointing when she skims over so many of the other portrayals (although her deconstruction of The Other Boleyn Girl is a lot of fun).

That gets us to Wolf Hall. The book and the show focus on Thomas Cromwell and his own rise to power in Henry’s court. He starts as an aide to Wolsey, witnesses his downfall, and helps Henry achieve his desired divorce from Catherine and marriage to Anne. The show often remains true to the book and brilliantly brings it to life. Mark Rylance is fantastic as Thomas Cromwell. But ultimately, the show stumbles somewhat. In Hilary Mantel’s book Wolf Hall, the action stops before Anne is thrown from power, before her final miscarriage. The next book, Bring Up the Bodies focuses on an incredibly short span of time. Whereas Wolf Hall spans maybe 10-15 years (with flashbacks to Cromwell’s childhood), Bring Up the Bodies focuses tightly on Anne’s downfall, the span of about a year. The show condenses both books into six episodes.

Most adaptations do not focus closely on Anne’s downfall. Maybe doing an entire six episodes on finding evidence, torturing Mark Smeaton, and holding multiple trials would not make for riveting television. But I couldn’t help feeling that the television adaptation sped through the process. They needed to get to the end and make Anne sympathetic as quickly as possible. I bought it with the BBC adaptation because I thought Claire Foy, who plays Anne, is charming and convincing. Anne is obsessed with her position and remaining in charge, but she didn’t come across solely as a conniver for me. Looking at other people’s reactions online, not everyone pitied Anne. Granted, you could argue the show is from Cromwell’s perspective and from his perspective, she was kind of an asshole. But I don’t think it’s fair to show Anne as a power-grabbing jerk and then do a 180 and make her a tragic figure once her downfall starts.

By turning Bring Up the Bodies into a full mini series in its own right, I think the show could have delved into more subtlety. Looked at how slightly inappropriate actions over time might mean nothing until suddenly someone starts gathering them all together. By taking multiple episodes to show Anne and those around her saying things that could be dismissed as flirting until the malicious intent comes into play, I think you could make an interesting drama about a woman who unknowingly plays a hand in her own destruction. In one episode, flirting with a courtier briefly would seem like the thing a queen should do, but it wouldn’t be until three episodes later that the audience would see how Cromwell can wield it against her. Maybe with a different husband or in a different time, Anne would have never come under suspicion. But as it was, in the wrong place at the wrong time, Anne is the wrong sort of woman to survive the time in which she lives. That portrayal would allow someone to see how something that builds over time can boil over in an instant and how maybe Anne was a bit more complicated than we typically think she was.

Which is why, at the end of it all, I have to give credit to The Creation of Anne Boleyn. Bordo recognizes the power Anne Boleyn holds over so many of us and how to a lot of women, she represents someone who is smart and headstrong and was able to do so much in a time when women weren’t supposed to do anything. She was so different and whatever you think about her, she managed to hold Henry in thrall for at least six years before he finally agreed to marry her. Not only that, but Anne’s had the power to hold sway over me and a whole host of others for the last five hundred years. A woman like that is something to be reckoned with.

Biography: The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn by Eric Ives – Often considered the definitive biography on Anne, Ives looks at court politics and what was going on around Anne, as well as what her role in the whole mess might have been. This latest version is an update from his original 1986 bio, and he takes the opportunity to counteract scholars who stand on more speculative ground.

Fiction: The Secret Diary of Anne Boleyn by Robin Maxwell – This book provides what historians can only dream about: Anne’s account of what happened to her in her own hand. The book takes liberties (there’s a lot of feminist thought for a sixteenth century woman) but it gives a deeply personal and psychologically rounded portrait. It also offers a frame story centering on Elizabeth I and her thoughts about her mother, which makes for an even more enticing draw.

Television: The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1970) – Not to be confused with a remake released a couple years after, which is not as good. In this TV mini-series, each episode was dedicated to one of the wives. Dorothy Tutin is possibly my favorite Anne Boleyn. She’s fierce and funny and strong and pitiable. She never got to question Mark Smeaton during her trial, but if she did, I imagine it would have gone something like this. I also highly recommend this series to anyone who wants to get a complex portrait of all of Henry’s wives.

Film: Anne of the Thousand Days (1969) – Genevieve Bujold is many people’s favorite Anne, and it’s no wonder. She’s witty and charming at the beginning and an absolute powerhouse at the end. Forget that Anne never would have blithely admitted to having casual sex before marriage (that’s the influence of the ‘60s) and that Henry never visited her in the Tower. Anne gets to chew on the scenery and that’s well worth the historical inaccuracies.

Featured image via BBC. The Tudors image via Showtime. Anne of the Thousand Days image via screengrab.