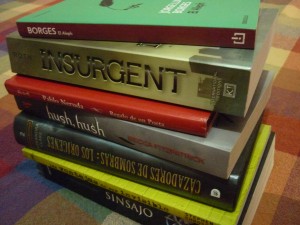

Young Adult literature is going through a gloomy phase, of sorts. It seems like everywhere you turn, there’s a new dystopian novel sitting on the shelf, eagerly awaiting its chance to depress the hell out of its young audience. Dystopian lit has even made its way onto the Hollywood stage with big budget hits like The Hunger Games, Divergent, and The Maze Runner. Full disclosure: I’m a 25-year-old woman with a full-time job who refuses to miss a midnight premiere of any of the Hunger Games movies. The appeal is universal.

So, what is it about this particular topic that’s made it such a mainstay over the past few years? Why is it so addictive?

A March 2015 discussion at MIT explored just this question. Entitled “Coming of Age in Dystopia: The Darkness of Young Adult Fiction,” the talk featured Graceling Realm series author, Kristin Cashore. The talk, inspired by Meghan Gurdon’s article “Darkness Too Visible” in The Wall Street Journal, debated the appeal of trauma in youth literature. Kenneth Kidd, professor and chair of English at the University of Florida, argued that trauma has always had a prevalent role in youth literature from Catcher in the Rye in the 1960s to Holocaust narratives, like Number the Stars, in the 1980s and 1990s. They certainly make a statement in the classroom. Both Animal Farm and I Am the Cheese were required texts in my eighth grade class, neither of which have a particularly cheery ending. While the presentation of trauma has shifted over time to cover different trends, novels dealing with intense, emotional topics have been popular for decades.

The dystopian novels that have become particularly prevalent over the past few years share similarities in structure to these older stories. Generally speaking, these stories feature some sort of totalitarian regime placing extreme limitations on its protagonists. It’s then the job of these protagonists to rebel against their oppressive leaders and reclaim their agency. It’s a story of the underdog triumphing over evil, where youth and inexperience don’t preclude these characters from becoming heroes.

These dystopian novels are symbolic for today’s youth. Children and teenagers are faced with limitations in every aspect of their lives. While in school, they’re shepherded from class to class by teachers and administrators; while at home, their parents dictate whether or not they can watch TV after doing their homework and whether or not they’re allowed to join different after-school activities. I was so relieved when I turned 16, not only because I had the freedom of the open road, but also because I no longer had to attend religious class once a week. I got an hour of my time back each week, and this small liberation was a huge personal victory.

These dystopian novels are symbolic for today’s youth. Children and teenagers are faced with limitations in every aspect of their lives. While in school, they’re shepherded from class to class by teachers and administrators; while at home, their parents dictate whether or not they can watch TV after doing their homework and whether or not they’re allowed to join different after-school activities. I was so relieved when I turned 16, not only because I had the freedom of the open road, but also because I no longer had to attend religious class once a week. I got an hour of my time back each week, and this small liberation was a huge personal victory.

Until the age of 18, children really don’t have much say about the direction of their own lives. And while this is done primarily to help protect them and allow them to successfully function in the adult world, children and teens still experience a certain amount of frustration from having everything decided for them.

Teenagers deal with limitations in different ways. Every parent dreads having a rebellious teenager. I think my mother was so willing to look the other way when I put an extra book in the shopping cart because as long as I was reading, I wasn’t getting into any mischief. Books were my tame outlet for dealing with teenage angst. For non-bookworms, rebellion is almost always associated with some sort of shift in identity, according to a 2009 article by Carl E. Pickhardt, Ph.D. from Psychology Today. Teens and pre-teens go through stages of wanting to shed their childhood images in favor of discovering who they’re meant to be as adults. Pickhardt explains that high schoolers often rebel just before leaving for college because they need to discover that they’re capable of being independent. Rebellion, therefore, becomes a necessary bridge needed to cross over into the unknown territory of adulthood.

The rebellion against authority, so prominently featured in dystopian literature, becomes a relatable experience for its youth audience. They get the opportunity to act out a fantasy, using the dystopian protagonists as conduits for their rebellion. Readers don’t feel the need to face the real-life consequences of dropping out of school and going on the run because their storybook heroes are the ones overturning their structured and limiting environments. Katniss can act out her frustrations by rebelling against the Capitol. Tris can run away from Dauntless. Teens and pre-teens feel satisfaction from the characters’ actions without the risk of failing out of school or committing a crime. I can vouch from personal experience that being an avid reader does actually pay off.

The dystopian structure also has quite a bit of appeal for adults. Kidd described authors that write for YA as going through a “schizophrenic orientation.” They have anxiety about young adulthood because they have vivid memories of that time in their lives.

Cashore admitted at the “Coming of Age in Dystopia” talk that there are parts of her novels that reflect issues she was dealing with in her own life, something she believes writers do often. The author writes about someone who is both them and not them all at once. There’s enough dissociation there to allow the author to work through some personal issues, both through the mask of youth and the mask of an alternate universe. The issues discussed in these dystopian YA novels continue to be relevant to adults today—just as they were relevant to the youth of the ‘70s or ‘80s.

I feel particularly connected to this genre. I was a ravenous reader in my youth and continue to read YA on occasion today. Good literature, after all, is good literature, regardless of the intended audience.

I feel particularly connected to this genre. I was a ravenous reader in my youth and continue to read YA on occasion today. Good literature, after all, is good literature, regardless of the intended audience.

I can distinctly remember what it meant to me to be a 15-year-old girl shut up in her room all Sunday consuming a book in one gulp. I read books because the process of growing up was strange and confusing, and I looked to literature as a way to find characters I connected with and to escape the humdrum of suburban life.

I was incredibly fortunate to have had a relatively safe and happy childhood, but that also meant that my life was rather sheltered and tedious. Books were my window to instant adventure, my way of learning about how life functioned beyond the tree-lined cul-de-sac. The Giver taught me the value of feeling pain and love; Lyra and Will taught me that you sometimes need to sacrifice your own desires to help the greater whole.

Dystopian novels, and all novels that deal with trauma, offer readers the safety of reflection through the lives of others. By experiencing trauma through the lens of a character in a book, I’ve become more empathetic to the plight of others and was better prepared to deal with difficult events I faced in my adult life. Dystopian YA doesn’t ruin a child’s innocence; it simply provides a separate environment for an adolescent to navigate the complicated issues with growing up. Parents can’t always prevent bad things from happening, but they can allow their children to develop the emotional and intellectual stamina to deal with issues head-on.

Header image via Enoksen. Teen zone image via Monterey Public Library. Insurgent image via Carlos Graterol.